Martin Brodeur played in his 1,250th NHL game–all with the New Jersey Devils–on Tuesday. It may have been his last night in the net in Newark. The face of the franchise, who hadn’t played in the previous seven games before his win against the Islanders on Saturday, wants to play for a team that wants to play him.

Isn’t that a positively devilish thought?

Brodeur gave the obligatory “can still play this game” line after last night’s 4-3 victory over the Detroit Red Wings. But at 41, and after a twenty-one-season tenure in New Jersey, for how long? Brodeur has provided the Devils with a list of “eight or nine” teams that would receive his approval if New Jersey worked out a trade. Devils fans discover by 3 p.m. today whether the familiar net-minder remains in New Jersey or gets shipped out.

The sight of Brodeur in a Minnesota Wild jersey, or wearing some other team’s gear, seems an obscenity on par with Mother Teresa trading duds with Miley Cyrus. We like Cal Ripken forever an Oriole, Bill Russell a permanent Celtic, and Terry Bradshaw always in black and gold.

But it doesn’t always work out on the field, ice, or court the way our imaginations want it to. So bizarre does O.J. Simpson wearing ’49er red and gold (let alone sporting jailhouse-jumpsuit orange) or Johnny Unitas on the Bolts instead of the Colts, strike us that our imaginations tell us that there’s something terribly wrong with reality. The surreal scene of a fatter, slower Dominique Wilkins barely able to dunk in Celtic green, or Patrick Ewing playing against the New York Knicks instead of for them, is enough to make us reach to adjust our television sets. It is, as I noted in an earlier piece, a venture into the Sports Twilight Zone.

You’re traveling through another dimension, a dimension not only of the sight and sound of rotting quarterbacks reverting to their ripened selves but of mindlessness; a journey into a wondrous land where athletes get better with age. That’s the goalpost up ahead — your next stop, the Football Twilight Zone.

Of course, what I wrote about Peyton Manning joining the Denver Broncos at the American Spectator a few years ago applies doubly so to Martin Brodeur minding net for a team other than the New Jersey Devils. Whereas Manning plays a cerebral position that relies on the head, Brodeur plays a position dependent upon quickness. Our decisionmaking gets better with age. Our reflexes? Not so much?

The late-career change of employers works for some. Ray Bourque won a Stanley Cup in Colorado that proved elusive to him in Boston. Joe Montana, and Manning for that matter, earned a place to play even when the the place where they played for so long could no longer give them that. But generally, the inability to say goodbye to a sport makes for a painful goodbye to a city.

Can you picture Franco Harris making the immaculate reception in Seahawks blue, Willie Mays chasing down a baseball with an over-the-shoulder circus catch in Shea Stadium, or Bobby Orr flying through the air as a Blackhawk after scoring in the Stanley Cup? There’s something positively unnatural about such thoughts. It’s like turning on CBS some Friday night in the 1980s and seeing Coy and Vance instead of Bo and Luke driving the General Lee.

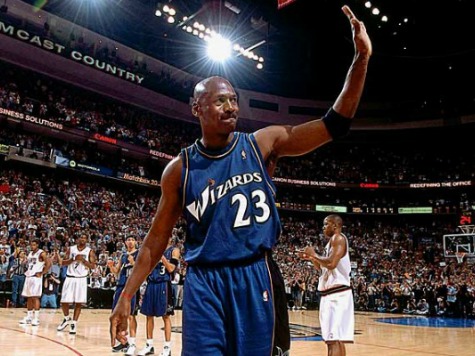

We like our athletes young and fast and strong. And images of them plying their trade on the teams when they were young and fast and strong is how we want to remember them. Michael Jordan on the Washington Wizards is a crime against our consciousness in a way that even 23 becoming 45, or the basketball player impersonating a baseball player, is not. Joe Namath in Rams blue-and-gold evokes pain–for the arthritic Namath and the fans forced to watch Broadway Joe become Hollywood Namath, a gimpy, graying guy who poorly portrayed the victor of Super Bowl III at the Los Angeles Coliseum on several Sundays in 1977.

Reality doesn’t always unfold the way it’s supposed to. Seeing Martin Brodeur tend goal in Minneapolis would affirm how false the truth often turns out.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.