Cyberspace Is Less Important than “Meatspace”

The coronavirus has reminded all of us—even the tech titans of Silicon Valley—that the digital and the virtual ultimately matter less than the physical and the biological. That is, it’s fun to be online, but what’s more important is to be alive.

Yes, surfing the Internet, sending texts, and streaming movies is of value to ordinary people—even if, of course, vastly greater value is reaped by those who own, say, Google, or Netflix, or AT&T. And yet today, all of us, toilers and tycoons alike, are being reminded that personal health means more than being well wired. Yes, Internet viruses are a pain, but the coronavirus is worse, because a malfunctioning computer isn’t as bad as a malfunctioning human body.

In other words, we’re reminded that for all the importance of cyberspace, our personal space—which techies sometimes call “meatspace”—is of much greater importance.

With that in mind, here in meatspace—also known as reality—we humans have to think about our ourselves, our families, and our fellow citizens. And as corporeal beings, we have to think also about our homes, roads, and jobs.

Indeed, we should think, in particular, about factories—because if the Chinese, for example, wish to infect us with some dangerous pathogen, we need a domestic medical-industrial complex for our own defense. (And of course, if the Chinese were ever to wish to nuke us or conquer us, we need other kinds of hardware, constantly upgraded, for our national security.)

How Silicon Valley Changed

Santa Clara Valley became Silicon Valley in the decades immediately after World War Two. In fact, as early as 1939, pioneering tech entrepreneurs William Hewlett and David Packard started building electronic instruments in their garage; nearby Moffett Naval Air Station became a hub for both purchases and innovation, soon spreading across the entire Department of Defense.

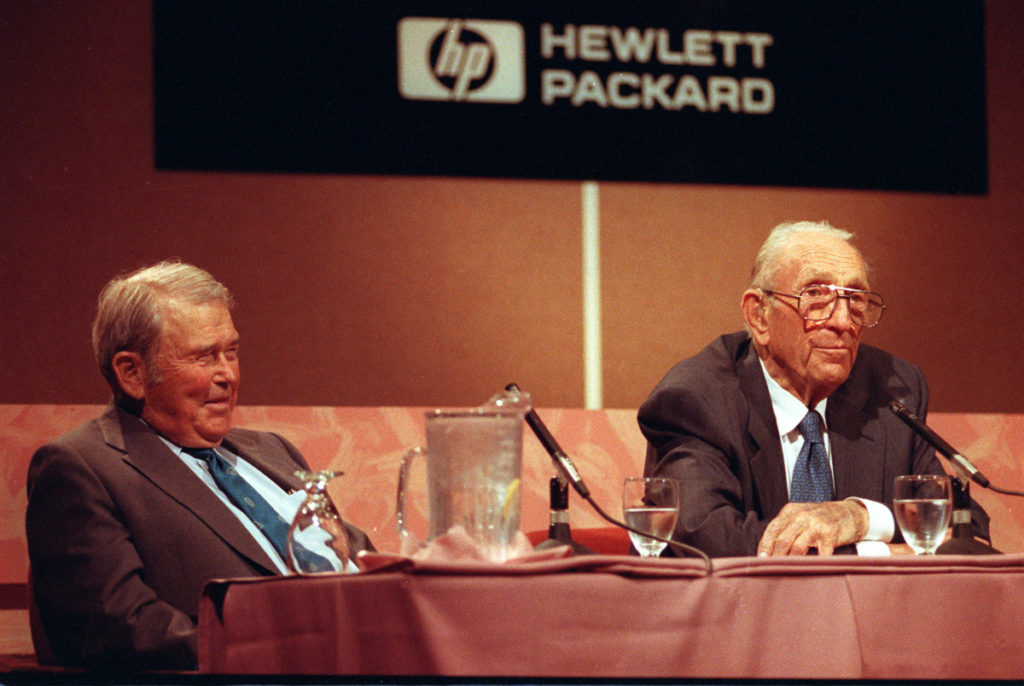

David Packard, right, co-founder of the Silicon Valley computer company Hewlett-Packard, announces his retirement as chairman during a news conference at HP’s headquarters in Palo Alto, California, on Sept. 17, 1993. Packard, 81, started the company in 1939 with William R. Hewlett, who listens at left. (Joe Pugliese/AP Photo)

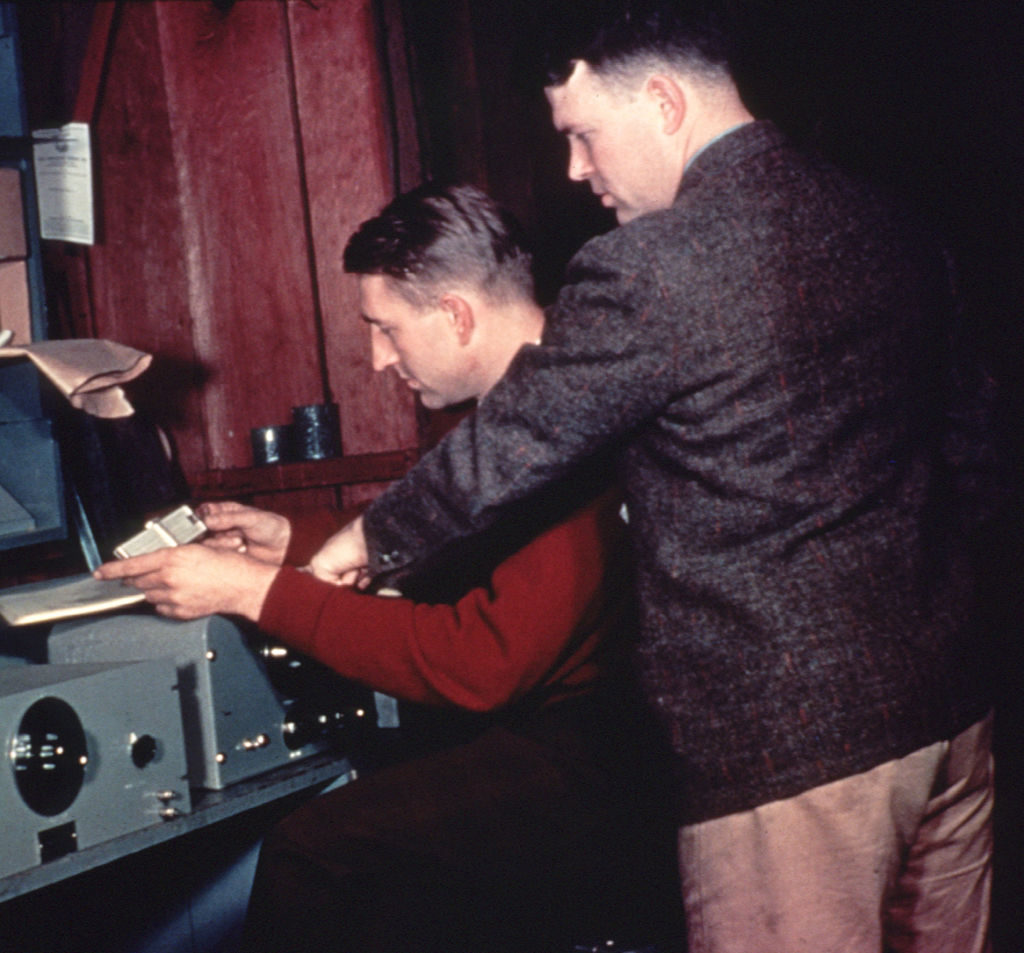

Hewlett-Packard co-founders David Packard (seated) and William Hewlett run final production tests on a shipment of the 200A audio oscillator. The picture was taken in 1939 in the garage at 367 Addison Avenue, Palo Alto, California, where they began their business. (Hewlett-Packard/Newsmakers via AP Photo)

Construction of Hangar One at NAS Sunnyvale (later renamed NAS Moffett Field) circa 1931–1934. (NASA)

Testing advanced designs for high-speed aircraft, June 1, 1948, an engineer makes final calibrations to a model mounted in the 6 x 6 Foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Ames Aeronautical Laboratory at Moffett Field. (NASA)

The Republic F84F Thunderjet fighter-bomber used by the United States Air Force was one of several high speed aircraft involved in flight research at the NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory (now, NASA Ames Research Center) at Moffett Field. Photo taken September 16, 1954. (NASA)

We can step back and observe that this early iteration of Silicon Valley was closely linked to practical applications; that is, the Valley was focused on gadgets and machines that helped us fight our wars.

Yet since the end of the Cold War, Silicon Valley has changed; it has shifted to a new and far more profitable focus, namely, slaking consumer demand. As we all know, Big Tech has focused on the virtual—that is, on new and better ways to search, to send e-mails and texts, to post things online, and to crunch data. To be sure, there’s nothing wrong with finding new ways to communicate, even if, of course, we haven’t adequately forestalled the disruption of other industries, including, but hardly limited to, media and publishing.

Indeed, Silicon Valley, as an ever-charging engine of virtuality, has seemed to be unstoppable. Thus prominent tech venture capitalist Marc Andreessen was inspired to write in 2011, “Software is eating the world.” We can recall that Andreessen first burst into prominence by developing the Mosaic browser for Netscape in the early 1990s; since then, he has invested in such virtual-product companies as Facebook, Groupon, Skype, Twitter, Zynga, and LinkedIn.

As Andreessen put it a decade ago, cheering on his business:

More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.

Marc Andreessen, left, and Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg speak during the Fortune Global Forum on November 3, 2015, in San Francisco, California. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

It’s interesting to recall that one of few voices running counter to Andreessen was that of another tech mogul, Peter Thiel, who declared in 2011, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” (Thiel was referring, of course, to the limits imposed by Twitter on the number of characters in a tweet; the limit has since been increased to 280.)

Thiel’s deeper point was that if Andreessen’s software-centric view prevailed, then progress in the world of hardware would likely continue to falter—and that’s why we can send tweets but not go flying around in Jetsons-type vehicles.

Peter Thiel speaks at the National Press Club October 3, 2011, in Washington, DC. Thiel argues that the United States and its leaders are on the wrong track regarding scientific innovation and that “when tracked against the admittedly lofty hopes of the 1950s and 1960s, technological progress has fallen short in many domains.” (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Indeed, an over-emphasis on the digital realm has come at the expense of the physical environment—which techies often call the analog world. After all, if you can work from home, then why worry about physical infrastructure, such as roads and bridges? And if you could freely surf the World Wide Web from your couch, why worry about national borders and a country’s sovereignty? And if you don’t worry about borders and countries, then why worry about your countrymen?

In the advanced tech lingo of the digital elite, geographic demarcations are simply “errors,” to be worked around by clever programmers and hackers—and the nation state is therefore said to be obsolete.

The Paradox of Slow Growth in the Digital Era

This idea of rampant digitalization has had consequences, to be sure—severe consequences. An important article appearing in The Atlantic in January was headlined, “The Real Trouble With Silicon Valley: The toxicity of the web is peanuts compared with Big Tech’s failure to remake the physical world.” As author Derek Thompson put it:

The digital age has coincided with a slump in America’s economic dynamism. The tech sector’s innovations have made a handful of people quite rich, but it has failed to create enough middle-class jobs to offset the decline of the country’s manufacturing base, or to help solve the country’s most pressing problems.

Continuing in that vein, Thompson added:

Decades from now, historians will likely look back on the beginning of the 21st century as a period when the smartest minds in the world’s richest country sank their talent, time, and capital into a narrow band of human endeavor—digital technology. Their efforts have given us frictionless access to media, information, consumer goods, and chauffeurs. But software has hardly remade the physical world. We were promised an industrial revolution. What we got was a revolution in consumer convenience.

That is, we have a lot of gig companies, such as Uber, Instacart, and Doordash, which is nice—even if, paradoxically, they rely mostly on old-fashioned people. And sadly, in the new order created by Silicon Valley, the algorithms have not enriched many workers, but have, rather, impoverished them. The machines, having broken down old industries, now assign displaced workers to drudge tasks, paying them only paltry sums—as insecure contractors, not as secure employees.

Not surprisingly, this bifurcating society—plutocrats and peons—is not a strong society, because what’s missing is a robust middle class that anchors institutions in comfortable stability.

Nor, interestingly enough, does this bifurcation lead to a strong economy, because the gains from productivity growth are mostly captured by the one percent of entrepreneurs and investors. Such top-heaviness, of course, leads to over-financialization and under-consumption.

In fact, Thompson points out that economic growth in the digital era has actually been slower—80 percent slower—than it was in the pre-digital era. He cites Chad Syverson, an economist at the University of Chicago, who has found that the slowdown in the economy, just since 2004, has cost the U.S. $2.7 trillion.

No wonder Peter Thiel, that tech renegade who has always cared about the physical United States, and its citizens, endorsed Donald Trump in 2016.

In the meantime, today we find that our “American” defense contractors are dependent on Mexico for key parts of their supply chains. In the tech-idealized borderless world, this is fine. In the real world, it’s not fine.

As George Mason University economist Alex Tabarrok wrote on April 26, this decline in our domestic productive capacity is “killing us.” As he put it, “The failure to spend on actually fighting the virus with science is mind boggling.”

It is, Tabarrok continued, “A rot … a failure of imagination and boldness which is an embarrassment to the country that put a man on the moon.” He noted, for example, that the share of the federal budget going to research and development has fallen from 12 percent in the 1960s to three percent today. “We are great at spending on welfare and warfare,” he concluded, “but all that spending has crowded out spending on innovation and now that is killing us.”

Let’s pray that it’s not too late to save ourselves, and our country. And then let’s get to work.

A Convert in Silicon Valley

This year, almost a decade after he celebrated the triumph of software, Silicon Valley’s Andreessen has chosen to celebrate hardware, actual construction, and an overall commitment to remaking our physical environment. Perhaps the onslaught of the virus has convinced Andreessen that more tweets won’t save us. In an April 18 essay, “It’s Time to Build,” he argued:

Every Western institution was unprepared for the coronavirus pandemic, despite many prior warnings. This monumental failure of institutional effectiveness will reverberate for the rest of the decade, but it’s not too early to ask why, and what we need to do about it.

Andreessen further attacked “smug complacency, this satisfaction with the status quo and the unwillingness to build,” adding, “You see it throughout Western life, and specifically throughout American life.” Warming to his theme, he continued:

You see it in manufacturing. Contrary to conventional wisdom, American manufacturing output is higher than ever, but why has so much manufacturing been offshored to places with cheaper manual labor? We know how to build highly automated factories. We know the enormous number of higher paying jobs we would create to design and build and operate those factories. We know—and we’re experiencing right now!—the strategic problem of relying on offshore manufacturing of key goods.

Andreessen added, where are the “giant, gleaming, state-of-the-art factories producing every conceivable kind of product, at the highest possible quality and lowest possible cost—all throughout our country?”

He had still more questions: “Where are the supersonic aircraft? Where are the millions of delivery drones? Where are the high speed trains, the soaring monorails, the hyperloops, and yes, the flying cars?” That reference to “flying cars,” of course, was a backhanded admission that Peter Thiel had the right idea a decade ago, because, yes, flying cars—and the technology that goes into them— are more important than tweets.

It’s certainly heartening to have Andreessen on the side of human beings and their needs; now we’ll have to wait and see how he, and his fellow tech titans, choose to follow up. Indeed, we might even hope that the digital transformation of the last few decades has just been a warm-up for the coming physical transformation over the next few decades.

In fact, there are some promising indicators, suggesting that progress in the digital space will translate into progress in the medical space. For instance, an intriguing article appeared in the Wall Street Journal on April 27, headlined, “The Secret Group of Scientists and Billionaires Pushing a Manhattan Project for Covid-19.” (We can recall, of course, that during World War Two, the Manhattan Project developed the atomic bomb; it’s hard to think of anything more physical than that.) This new group hopes, for example, to transform the Food and Drug Administration, so that it can move with Moore’s Law speed.

In fact, World War Two saw a Pentagon-sponsored surge in many technologies beyond nuclear, providing our fighting men with radar, penicillin, synthetic rubber, and even new kinds of fabrics, designed to be used for everything from uniforms to parachutes. Indeed, it’s fair to say that the Good War was won as much on the homefront—in our laboratories and factories—as it was on the battlefront.

And of course, after the war, these technologies were spun off into the civilian sector. Thus we can see the origins of the big economic boom of the three decades after the war—you know, the boom that’s ebbed in recent decades.

Amidst the Current Carnage, Signs of Real Hope and Change

As our great wartime president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, said famously at the beginning of his time in the White House, “The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.”

So now today, as we confront the reality that we’re in another war—a war against the virus—we should take heart in the fact that we have plenty of resolve and resources. And if we do take heart, we can overcome fear.

Indeed, if we buckle down and apply what we know—and figure out what we must learn—we can win this war and come back even stronger. We can, in fact, Make America Great Again. Much of that greatness, of course, will come from our own ingenuity and knowhow; indeed, it might have nothing to do, at least at first, with Silicon Valley, and everything to do with the Heartland.

For instance, just on April 30 came a report from Marcellus Drilling News, a publication devoted to the shale-gas industry in the Northeast, taking note of an astonishing new breakthrough in carbon-based fuels.

Researchers at Penn State University’s EMS Energy Institute, joined by H Quest, a Pittsburgh-based start-up, have found a way to “burn” natural gas, generating usable hydrogen while at the same time reducing carbon dioxide emissions to zero. As the article explains, this joint partnership:

… may hold the answer to reducing so-called greenhouse gas emissions while also paving the way to disrupt the chemical and material industries. The collaboration has resulted in several research projects that aim to “reinvent” both coal and natural gas as clean, cost-effective sources of fuels and high-performance materials. … Penn State and a company called H Quest are extracting hydrogen from nat gas using microwave plasma technology. It’s completely free of so-called greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, microwave plasma enables smaller, modular chemical conversion plants-cheaper to build and deploy.

The prospect here is epic: We can preserve our carbon-based fuel industry, as well as the many millions of jobs it creates and supports, and still have an environment that might put a smile on the face of that pouting teen, Greta Thunberg. (Okay, probably not—some greens dislike everything.)

In fact, if this new technique can cleanly distill hydrogen not only from natural gas, but also from oil and coal, then we could have all the domestic energy we need for hundreds, even thousands, of years. And that would surely be the beginning of a long-term economic boom for places that need, and deserve, better times.

So maybe here is a project in which Marc Andreessen can invest, bringing the significant value-add of the latest digital tech to this new energy tech.

If so, that’s how we get the money to start building up the country again. And that’s how we start reuniting our people, aligning the red of carbon country with the blue of silicon country.

Together. That’s how we go about saving our nation—in this time of grave peril.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.