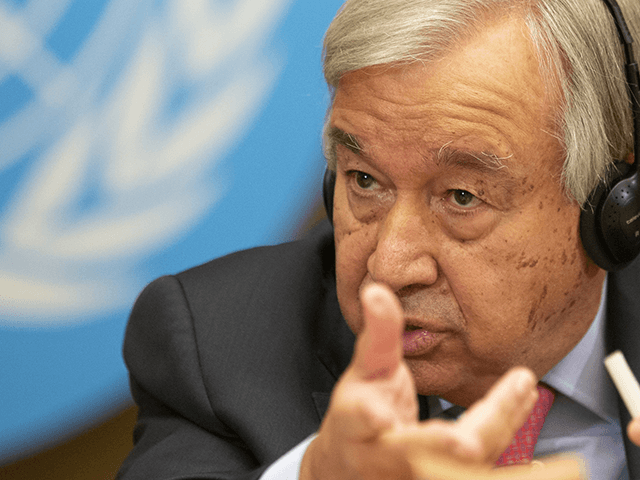

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on Monday touted his proposal for a “Global Digital Compact,” which would include planet-wide laws against “hate and lies in the digital space.”

The proliferation of hate & lies in the digital space is causing grave global harm.

This clear & present global threat demands clear and coordinated global action.

We don’t have a moment to lose.

My proposals for a Code of Conduct: https://t.co/7R0Hujf3y5 pic.twitter.com/jnEozVr76K

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) June 12, 2023

“Digital platforms are being misused to subvert science and spread disinformation and hate to billions of people,” Guterres said.

“The proliferation of hate and lies in the digital space is causing grave global harm. This clear and present global threat demands clear and coordinated global action. We don’t have a moment to lose,” he declared.

Guterres said the U.N. policy brief on “Information and Integrity on Digital Platforms” provides a “framework” for a suitable coordinated international response.

The U.N. has actually published two related policy briefs demanding globalist control of the Internet. The first one, the Global Digital Compact, is primarily concerned with eliminating the “divide across regions, gender, income, language, and age groups” for Internet access, pointing to such factoids as “some 89 percent of people in Europe are online, but only 21 percent of women in low-income countries use the Internet.”

“Inequality is rising,” the U.N. policy brief declared. “Enormous investments in technology have not been accompanied by spending on public education and infrastructure. Digital technology has led to massive gains in productivity and value, but these benefits are not resulting in shared prosperity.”

The Global Digital Compact included several complaints about “hate speech” and “disinformation,” which it linked with malicious hackers, criminal activity, authoritarian state controls, and “predatory business models” as “serious risks to human rights.”

One of the objectives of the Global Digital Compact is to develop “robust accountability criteria and standards for digital platforms and users to address disinformation, hate speech, and other harmful online content.”

This idea was greatly expanded upon in the “Information Integrity on Digital Platforms” policy brief Guterres referenced in his remarks on Monday. This document railed against the “darker side of the digital ecosystem,” which has “enabled the rapid spread of lies and hate, causing real harm on a global scale.”

“The danger cannot be overstated. Social media-enabled hate speech and disinformation can lead to violence and death. The ability to disseminate large-scale disinformation to undermine scientifically established facts poses an existential risk to humanity,” the paper said.

These diagnoses and alarm tones are also a brief and effective summary of why passing global laws against “hate speech” or “disinformation” is an unlikely remedy and one that should alarm everyone concerned with free speech. To put it mildly, big global organizations have not exactly covered themselves in glory as dispassionate arbiters of hatred or scientific truth over the past few decades, and especially during the Wuhan coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath.

The general public in the free world has probably never been less likely to agree that some transnational body should be appointed as the ministry of absolute, impartial truth. The unfree world would either refuse to let a U.N. body police it for hatred and disinformation – or, more disturbingly, would subvert such a body to enforce the policy preferences of authoritarian regimes. It is not difficult to imagine what the Chinese Communist Party would insist was actionable “disinformation” about topics such as the origins of the Wuhan coronavirus, the Uyghur genocide, or the Tiananmen Square massacre, for example.

The U.N. policy brief admitted that “the distinction between mis- and disinformation can be subtle and difficult to determine” – but even that says nothing about the difficulty of distinguishing between disinformation and politically incorrect truth, or between misinformation and debatable opinion.

Disturbingly, the U.N. policy brief veered into several highly politicized topics, especially regarding climate change, which the U.N. clearly sees as a settled issue upon which the arbiters of global absolute truth can comfortably pass judgment.

One of the “misinformation” tactics the U.N. is evidently eager to regulate is “greenwashing,” defined as “misleading the public into believing that a company or entity is doing more to protect the environment, and less to harm it, than it is.” There is no way the money-saturated, hyper-politicized climate movement can be trusted to decide what constitutes “greenwashing.”

The U.N. also sees itself taking a role in “disinformation” policing during elections, where “the spread of mis- and disinformation can undermine public trust in electoral institutions and the electoral process itself.”

Such an ambition is likely to prove even more contentious for the U.N. than setting up global ministries of truth and science. In the United States, both parties have histories of challenging election outcomes. Which challenges will the U.N. decide are unacceptable disinformation, and which would it excuse as spirited politicking?

The policy briefs Guterres touted talked at great length about how huge the Internet is, and how serious the problems of online hatred and disinformation have become, but there was not much nuts-and-bolts discussion of how worldwide policies against dangerous speech would be formulated or enforced.

The closing pages of the Information Integrity brief praised some existing regulatory responses such as the European Union’s Digital Services Act of 2022, applauded some private digital platforms for voluntarily adopting “some kind of system of self-regulation, moderation, or oversight,” and took a moment to salute the effectiveness of U.N. campaigns against disinformation – but Guterres clearly envisioned something more centralized and muscular.

The Code of Conduct proposed at the end of the document laid out some lofty goals, but no details for how they would be implemented, or how violations would be judged.

For instance, it urged U.N. member states to “ensure that responses to mis- and disinformation and hate speech are consistent with international law, including international human rights law, and are not misused to block any legitimate expression of views of opinion.”

That will obviously be a non-starter in China, Russia, and other authoritarian regimes and, judging by the rest of the document, the U.N. probably would not get too upset if “responses to disinformation and hate speech” were abused to block legitimate criticism of the climate change movement.

“Digital platforms should move away from business models that prioritize engagement above human rights, privacy, and safety,” the Code of Conduct demanded. That will be a tough sell over at the Chinese offices of ByteDance, the owner of TikTok.

The U.N. called on platform owners to “invest in human and artificial intelligence content moderation systems,” but those are among the most controversial topics in the debate over freedom of speech at the moment, as algorithms and A.I. systems can clearly be programmed to impose political prejudices.

“From health and gender equality to peace, justice, education, and climate action, measures that limit the impact of mis- and disinformation and hate speech will boost efforts to achieve a sustainable future and leave no one behind,” the policy paper concluded. There is no great consensus of people in the free world, or ruling party officials in the unfree world, who trust the United Nations to regulate, or even define, any of those things.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.