A Trumpier Fed Isn’t An Inflation Threat

The financial press has been trying its best for months to gin up a panic over the independence of the Federal Reserve.

We’ve had a number of dress rehearsals for the supposed death of Fed independence over the last few years. When President Trump started criticizing Fed chairman Jerome Powell during the first Trump administration, the media falsely insisted that it was an unprecedented attack on the central bank. When Trump announced the removal of Lisa Cook, a Fed governor who was previously best-known for exactly nothing, it was treated as an existential crisis.

Now we’re approaching peak media panic. President Trump’s expected nomination of Kevin Hassett to replace Jerome Powell has triggered dire warnings from economists and pundits about the end of central bank credibility. The narrative goes something like this: Trump will install a loyalist who’ll cut rates recklessly, inflation will spiral, and the bond market will revolt.

There’s a big problem with this story: the bond market isn’t buying it.

Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal recently noticed something curious in the data. Despite non-stop chatter about the Fed abandoning its inflation mandate under the leadership of whoever Trump appoints, market-based measures of future inflation expectations remain remarkably calm. The five-year, five-year forward inflation expectation—a measure of where traders expect inflation to go in the five year period that starts five years from now—sits near post-2024 election lows. As Weisenthal notes, “you would never know that there is non-stop chatter about the Fed giving up on its inflation goals” just by looking at the charts.

Weisenthal quotes Steven Englander, macro strategist at Standard Chartered. “Questions have been raised about Kevin Hassett’s credibility with markets and within the FOMC, but the questions are not showing up so far in inflation breakevens,” writes Englander. “If Hassett as Federal Reserve Board Chair is expected to compromise inflation outcomes, this is where we would expect to see these concerns most clearly.”

And it’s not just market-based measures. The survey data tells the same story across the board.

The Data Speaks: Inflation Expectations Are Cooling

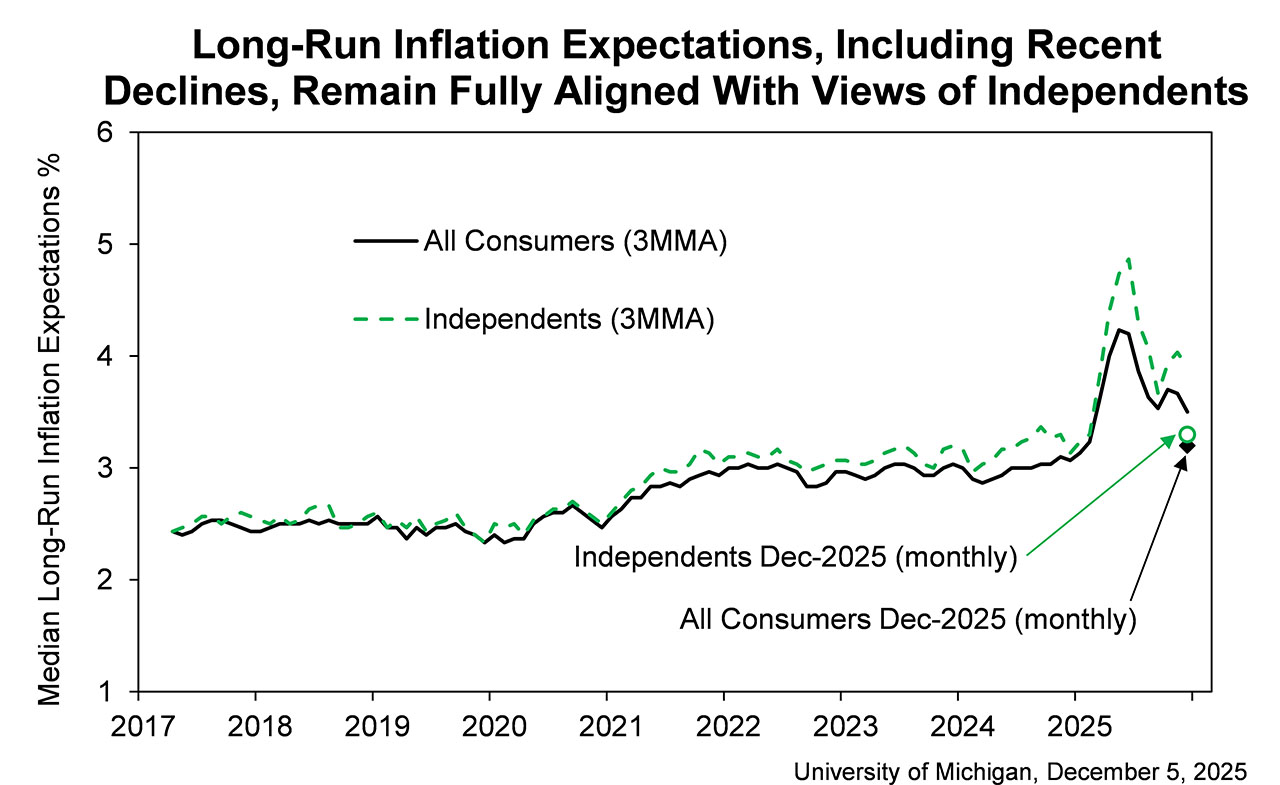

The University of Michigan’s December survey shows consumer inflation expectations falling for the fourth straight month. Year-ahead expectations dropped to 4.1 percent, the lowest reading since January 2025. Five-year expectations eased to 3.2 percent, matching the January level.

The New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations paints an even more benign picture. November data shows median inflation expectations holding steady at 3.2 percent for the one-year horizon and 3.0 percent for both three-year and five-year horizons. These figures have been remarkably stable for months.

Perhaps most tellingly, the Atlanta Fed’s Business Inflation Expectations survey—which captures the views of actual price-setters in the economy—shows firms expecting just 2.2 percent inflation over the next year as of October. That’s down from a peak of 3.8 percent in April 2022 and nearly back to the pre-pandemic average of 2.0 percent.

These aren’t politicians or pundits guessing about inflation. These are businesses making capital allocation decisions, consumers planning purchases, and traders with billions of dollars on the line. None of them are panicking about a Trump appointee-led Fed abandoning price stability.

The Market Has Updated Its Priors

So what’s going on? Why aren’t markets freaking out about Fed independence?

Here’s what the Fed independence discourse misses: market calm about Hassett (or whoever Trump eventually picks) doesn’t necessarily mean traders are complacent. It might mean they’ve learned something the economics establishment hasn’t: that the pre-2025 consensus framework has been wrong about inflation dynamics.

Consider what the expert class predicted over the past few years. Most recently, it insisted that tariffs would cause runaway inflation. We were told Trump’s trade policies would devastate consumers with massive price increases. Harvard Business School’s tariff price tracker tells a different story. The feared inflation spike never materialized. University of Michigan survey director Joanne Hsu explicitly noted in December that “consumers noted that concerns of tariff-related surges in prices have not come to fruition.” Maybe traders remember this when they hear warnings about Hassett.

Earlier, we were told we couldn’t bring inflation down without a recession. The consensus in 2022 and 2023 held that reducing inflation from 9 percent to 2 percent required significant labor market pain—Larry Summers famously suggested we’d need years of 6 percent unemployment. Instead, inflation fell rapidly while unemployment stayed below 4 percent. The models were wrong.

Supply-Side Confidence and a New Real Neutral Rate

Markets may also be pricing in confidence about Trump’s broader economic agenda. Deregulation, energy production expansion, and productivity gains all have disinflationary potential through the supply side. If you believe Trump’s policies will increase productive capacity, you can run a more accommodative monetary policy without risking inflation.

Stephen Miran, who headed the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers until he was appointed by Trump to a short term seat at the Fed, delivered a September speech laying out why current policy is “well into restrictive territory” and potentially 2 percentage points too tight.

Miran’s core insight is that major policy changes in 2025—particularly around immigration and fiscal policy—have dramatically reduced the neutral rate in ways that backward-looking models miss. He argues that reduced immigration is lowering population growth from 1 percent annually to perhaps 0.4 percent, which research suggests reduces the neutral rate by nearly 0.4 percentage points. Meanwhile, tariff revenues and reduced deficits from the “One Big Beautiful Bill” are increasing national saving by over 1 percent of GDP, which pushes the neutral rate down by another half percentage point through reduced demand for loanable funds.

Add in the effects of deregulation increasing productive capacity, and Miran calculates that the real neutral rate—that is, how high the policy rate needs to be above the rate of inflation in order to be neither a drag nor an accelerant in the economy, which economists like Miran call “R*”—may be near zero, far below conventional estimates. Using a weighted average of model-based and market-based measures, he argues the appropriate federal funds rate should be around 2 percent to 2.5 percent, not the current 4.5 percent.

If Miran is right that these structural policy changes have fundamentally altered the supply-demand balance for capital, then current rates represent far more economic drag than conventional wisdom acknowledges. This would explain both why inflation has cooled so quickly despite doomsaying, and why markets aren’t panicking about Hassett cutting rates. They may simply believe the Trump administration’s read on the neutral rate is more accurate than estimates that haven’t fully incorporated the regime shift of 2025.

This isn’t “giving up” on the 2 percent target. It’s recognizing you can hit that target through different policy combinations. Hassett seemed to be embracing this view when he suggested at the Wall Street Journal CEO Council that there’s “plenty of room” to cut rates.

Trump Is Not An Inflationista

The establishment frames Fed independence as synonymous with “credible inflation fighting.” But that framing assumes the current committee has been fighting inflation credibly. Have they?

This is the same Fed that called inflation “transitory” throughout 2021. The same Fed whose staff economists consistently overestimated how much unemployment was needed to bring inflation down. The same Fed that has consistently warned that tariffs would push inflation higher, only to be humiliated by data and research showing no such thing occurred.

What if the market’s calm about Hassett reflects not complacency but a rational updating of beliefs? What if traders have concluded that monetary policy should be made by people who share Trump’s economic framework rather than by the committee and staff that’s been consistently wrong about inflation dynamics for five years?

There’s a final irony here. The recent Fed independence discourse assumes that giving Trump more influence over the Fed would result in higher inflation. This appears to be doubly wrong.

In the first place, the Fed managed to oversee inflation rising to its worst levels in forty-years while Joe Biden was president. Biden was very careful not to publicly pressure the central banks and reappointed Powell, who was originally tapped by Trump to run the Fed. Fed independence—if that’s what you want to call it—did not prevent policy from staying too loose for too long.

Second, there’s no good reason to assume Trump would push for an inflationary monetary policy. He ran on bringing down inflation and witnessed the political devastation high inflation inflicted on the Democrats in the 2024 election. He can read the polls that tell him that voters still say inflation is the biggest issue facing the nation. He certainly does not want the legacy of his administration to be a rebirth of Bidenflation.

The market seems to have figured this out. Trump’s critics and the financial media have not.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.