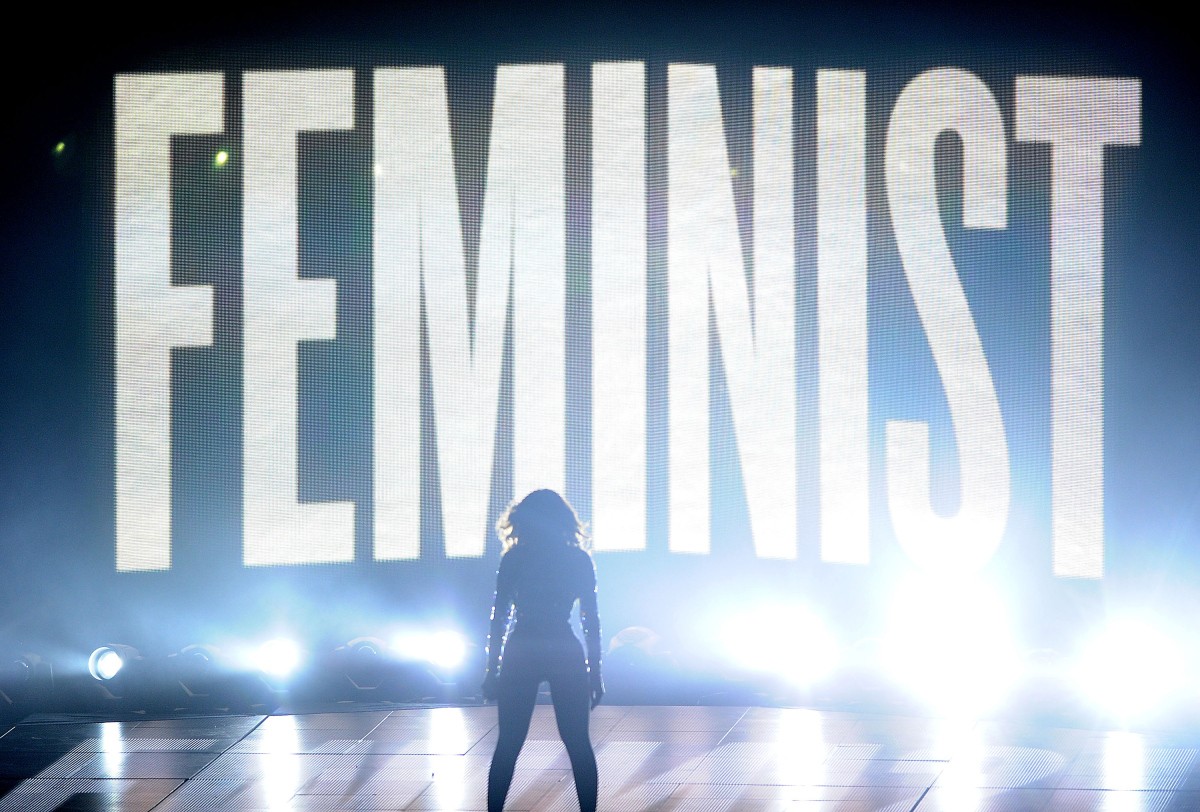

“FEMINIST” blared the stage behind Beyoncé at MTV’s Video Music Awards in August this year. No true megastar would feel the need to declare themselves on the subject one way or another, but the stunt was typical of the neediest, most inconsistent and most irritating pop artist of our age.

After all, the Texan Methodist gospel girl who grew up to be a star, and whose last tour was named “The Mrs. Carter Show World Tour,” in honour of her husband, is the last person today’s independently-minded, socially liberal, stridently atheist feminists ought to relate to.

In 2006, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter was a registered Republican voter, as were all of her immediate family members. “I grew up in a very nice house in Houston, went to private school all my life and I’ve never even been to the ‘hood,” she once told an interviewer, before quickly adding: “Not that there’s anything wrong with the ‘hood.”

She sang at Barack Obama’s inauguration, though not, she said at the time, because she sympathises with his political ideals. She has since hosted fundraisers for Obama but has never denied she goes home and votes for the GOP. Then again, she wasn’t entirely on board when she played for George W. Bush either: “I played at the inauguration because there were a lot of kids in the audience that I wanted to reach, that’s all,” she said afterwards. “Maybe one day I will speak of my political beliefs, but only when I know what I’m talking about.”

Wanting to speak but having nothing to say is a fair summary of the entire Beyoncé project. “She just wanted to be a normal child,” says her uncle, Larry Beyince. “She loved to watch cartoons and be with her friends. She was forced into singing. It took away her whole childhood. Everything was geared toward being famous. She used to get angry at [her father] a lot for taking away her childhood. That affected her.”

Beyoncé’s great artistic mistake has been to think that her personal frustrations should be hidden from the public, rather than marshalled as a creative force. We crave realness from our celebrities, to the point that reality stars are afforded endless column inches, no matter how odious they are, if they will only bare their souls to us. Great singer-songwriters have one biographical detail in common, above all else: they say that if it weren’t for music, they’d have died. They need to sing. We don’t get that from Beyoncé.

Beyoncé was railroaded into a singing career by her father, and, later, her husband. Jay Z groomed Beyoncé for stardom, some say in return for marriage. A recent, well-publicised dust-up in a lift between Jay and Beyoncé’s sister Solange is emblematic of the star’s ambivalence to family: she stood by impassively while an argument between her husband and her sibling spilled over into violence, only paying attention enough to move her dress out of the way. She came out the lift smiling.

It wasn’t the first time Beyoncé demonstrated cold-hearted indifference to family. She famously cut her parents out of her life shortly after their divorce, arguably the moment they ceased to be useful to her. She was furious at their insistence that she should be a star. But she became one anyway, trading in her father’s overbearing male presence for another alpha male, Jay Z. Her family, who in 1995 had taken a 50 per cent cut in household income, moving in to multiple, smaller apartments to give Destiny’s Child a shot, were left in the dust. And then, of course, watched by millions, she reduced her former bandmatesto the status of backup singers in her over-produced, overblown Superbowl half-time show.

To say Beyoncé is defined by her marriage is an understatement. Jay Z created and nurtured her celebrity in what looks a lot more like a business than a personal relationship–before, reportedly, cheating on her with Rihanna. Her relationship with the men in her life may explain why so many of Beyoncé’s lyrics go beyond “girl power” and into borderline misandry. It’s a cycle of dysfunction that continues with Blue Ivy, Beyoncé’s daughter by Jay Z. Blue Ivy is the most famous stage prop in the world. Even North West, Kim Kardashian and Kanye West’s baby, isn’t wheeled out so cynically.

Knowles-Carter has a reasonable claim to the title of loneliest woman in the world. In Beyoncé’s world, others are stars, but she is the Sun, emitting a light so blinding it excludes all other sources of radiation. Other artists are refracted through her, and intelligible only in terms of their distance from her. She is pop music’s Meryl Streep: an overbearing, vampiric creature who sucks life out of the rest of the world, and disappears from memory as soon as she leaves the stage. Her voice is technically spectacular, sure. But that’s all it is, and its technical wizardry leaves no space for feeling, and, thus, enduring memory.

That doesn’t mean she’s not confident–or, at least, that she doesn’t project confidence through spectacle. “I have an authentic, God-given talent, drive, and longevity that will always separate me from everyone else,” she once said, in response to a question about her rivalry with Rihanna. If you say so, dear.

* * *

The world has been failing Beyoncé in the last few years, mocking her clumsy attempts to muzzle photographers and her cowardice at the aforementioned inauguration: she bottled out of singing live, then had to be wheeled out at a press conference to belt an over-the-top, face-saving a cappella version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” We already knew she could sing. The question was why she hadn’t. What’s a chanteuse for, if she can’t sing live on the day?

That was the first of a series of signs that Beyoncé was annoyed with us for not recognising her transcendent brilliance. It’s an anxiety that never makes it into her music—more‘s the pity. There is no true agony in a Beyoncé record. What separates her music from the greats of the past–compare her frivolous riffs with the exquisite torture of late Billie Holiday album Lady in Satin–is the impression that she’s never known pain, and that her heart’s not really in all this. That’s not true of her contemporaries. No serious person pays attention to, or can even tell the difference between, those bland white girls Taylor Swift and Katy Perry. But consider Céline Dion, who is in so much pain she shares it with us every time she sings. Or Mariah Carey, whose defining professional characteristic is success against the odds.

In place of redemptive fables, those essential human experiences we look to our pop icons to make sense of, Beyoncé offers cold, theatrical certainty. “Why Don’t You Love Me” from 2008’s I Am… Sasha Fierce comes closest in the Beyoncé canon to delivering genuine anguish. But the video shows up the song’s failings: even at her most desolate, Beyoncé cannot bear the thought of being ugly. So she invents an aesthetic of despair more beautiful than any video she’d previously produced.

Part of the reason Beyoncé has lost spiritual purchase on listeners is that she has drifted from her faith. Her waffly, incomprehensible live interludes between songs and her non-committal answers in interviews, though drenched in thanks-be-to-God apophthegms, have less in common with her religious upbringing than they do the faux-spirituality of Oprah Winfrey. Predictably, Beyoncé and Oprah adore each other. Like Winfrey, she has left religion behind in favour of “spirituality,” convenient to both women because it is infinitely extensible, adaptable to circumstance and because, with God out of the picture, Beyoncé and Oprah are free to indulge their own gigantic egos. When Beyoncé says “God,” she means “Beyoncé.” Even Kim Kardashian has more intellectual integrity than that.

As the biggest pair of lungs in Destiny’s Child, Knowles-Carter revealed a self-awareness and humility that might have developed into an inspirational personality. When she sang in praise of the Lord in the late 1990s, we believed her: the Amazing Grace outro on 1999’s The Writing’s On The Wall is Beyoncé at her most ecstatically revealing and spiritually engaged. (The schmaltzy, self-conscious harmonies of the gospel medley on Survivor, two years later, have none of the same soul.)

But any trace of duty or reverence before God disappeared after 2003’s “Crazy in Love,” perhaps her last genuine expression of emotion. Beyoncé has become the deity she used to worship. Yet, for all her power and ubiquity, she remains the most radically insecure figure in the heavens, approving only those images of herself that project a spiritual and sexual serenity she has not worked to achieve in her personal life. She tried to have unflattering images from that Superbowl performance scrubbed from the internet (imagine it), and she has banned press photographers from her latest tour. Other stars use photo ops to send messages, but Beyoncé’s relationship with the camera tells us nothing, except that she is vain and controlling.

Beyoncé herself gives us a clue just how bad things are at home on the opening track of her self-titled 2013 album, BEYONCÉ. “My aspiration in life… would be… to be happy,” she confesses. If the preternaturally perfect Beyoncé’s not happy by now, what hope is there for the rest of us? And in there is the clue: once again, it’s not really her speaking. You can never quite connect with Beyoncé, and when you get close, you sense that there’s not a particularly likeable person underneath all the sequins and lace.

Like Lady Gaga, another unspeakably boring and over-rated performer, Beyoncé the artist has no dark double, no secret, amoral place from which her artistic motivation springs. She is an invention. She and Sasha Fierce, her supposed 2008 alter ego, share the same persona: flat, attention-seeking, brash. Beyoncé doesn’t appear to believe in anything and she isn’t wrestling with anything either. That’s alright for a lot of people, at least while she’s churning out records that make people feel good about themselves.

But you can’t have an enduring relationship with a brick wall, which is why, the moment Queen Bey stops releasing feel-good crowd-pleasers, you have to figure she will evaporate from popular consciousness. Perfection of a flippant, trivial sort define Knowles-Carter, from the pseudo-religious cult that surrounds her to the royal pretensions of her music videos. She is “Queen Bey” to her acolytes: a fierce, fabulous icon of strong female sexuality, married to Jay Z, one of the most powerful men in the business. It’s a wonder so many people think they identify with such fakery and vacuousness, and a tragedy that the real Beyoncé is so committed to evading authenticity and such a–dare I say it–laugh-free zone.

Although, given what we know about her private life, we might conclude that enjoying an uncomplicated façade is preferable to getting to know the woman. This is speculation, of course, because Beyoncé will never give us enough information to decide. (Even the word “Beyoncé” is made up, a riff on her mother’s maiden name, reimagined as an exotic-sounding epithet by overbearing, fame-hungry parents.)

Crass pyrotechnics, sexual titillation and ego boosts for the sisterhood are unconventional routes to female empowerment. But it is what we have come to expect from Beyoncé, in whom it is the male idea of female beauty that finds highest and most perfect expression. She is what men demand of her, less than the sum of her body parts. Living art, but art that says remarkably little. Her collaboration with Gaga on Telephone was a perfect marriage; the empty masquerading as the enigmatic.

Beyoncé is a success as a pop star but a failure as an artist, which makes the rabidity of her enormous fan base, the “BeyHive,” a bit saddening. Perhaps Beyoncé’s cultic following is a product of our time. Certainly, the fetishisation of the insubstantial takes many forms, Beyoncé-worship perhaps the most obvious. She is a pop star for people who refuse to think. Maybe that is why, when she reaches for profundity, she stumbles. “Halo,” which often closes out her shows, is cited as her greatest achievement. But, like her voice, it is thin, reedy and unsatisfying: a spectacle of pomp, signifying nothing.

It’s a song whose lyrics are about stripping down walls and showing the real person inside, but musically speaking it’s the most superficial and manipulative record she’s ever released. Everything Beyoncé does is predictable, but “Halo” is the most predictable, timorous, trashy anthem of the last two decades. Its climax serves up empty ineffability, like a bad Philip Larkin poem. It is, like so much of what Knowles-Carter does, trying too hard.

Real artists don’t have to tell you to bow down, and, when they speak, they bring something fresh. But when Beyoncé demeans herself with attempts to “do politics,” such as her terrible mini-essay on gender equality, which an Oberlin freshman would have been embarrassed by, it’s simply another way for her to scream: “Please love me.” Everyone wants to be loved, but Beyoncé scales new heights of desperation in demanding reverence while providing no emotional sustenance or intellectual nourishment to her subjects. If she were capable of humour, we might have written off her “FEMINIST” statement as a clever provocation. But she is probably the least funny, least cerebral star in the cosmos, so we can’t.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.