AFP — On February 14, 1989 Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini called for British writer Salman Rushdie to be killed for writing “The Satanic Verses”, which the cleric said insulted Islam.

In a fatwa, or religious decree, Khomeini urged “Muslims of the world rapidly to execute the author and the publishers of the book” so that “no one will any longer dare to offend the sacred values of Islam.”

Khomeini, who was 89 and had just four months to live, added that anyone who was killed trying to carry out the death sentence should be considered a “martyr” who would go to paradise.

A $2.8-million bounty was put on the writer’s head.

– Driven underground –

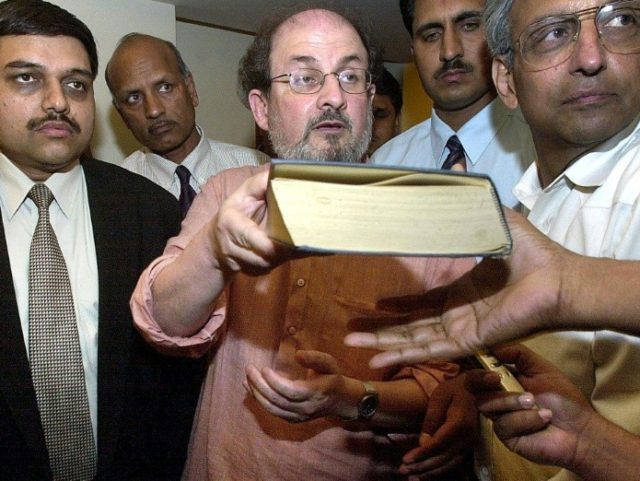

The British government immediately granted police protection to Rushdie, an atheist born in India to non-practising Muslims.

For almost 13 years he moved between safe houses under the pseudonym of Joseph Anton, changing base 56 times in the first six months.

“I am gagged and imprisoned,” he recalled writing in his diary in his 2012 memoir, “Joseph Anton”.

“I can’t even speak. I want to kick a football in a park with my son. Ordinary, banal life: my impossible dream.”

– ‘Blasphemous’ –

Viking Penguin published “The Satanic Verses” in September 1988 to critical acclaim.

The book is set by turns in the London of Conservative British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and ancient Mecca, Islam’s holiest site.

It centres on the adventures of two Indian actors, Gibreel and Saladin, whose hijacked plane explodes over the English Channel.

They re-emerge on an English beach and mix with immigrants in London, the story unfolding in surreal sequences reflecting Rushdie’s magic realism style.

The book was deemed blasphemous and sacrilegious by many Muslims including over references to verses alleged by some scholars to have been an early version of the Koran and later removed.

These verses allow for prayers to be made to three pagan goddesses, contrary to Islam’s strict belief that there is only one God.

Controversially, Rushdie writes of the involvement of a prophet resembling the founder of Islam, Mohammed.

This prophet is tricked into striking a deal with Satan in which he exchanges some of his monotheistic dogmatism in favour of the three goddesses. He then realises his error.

Khomeini and others insist he had depicted the prophet irreverently.

Authors in Search of Some Character: Salman Rushdie Calls Charlie Hebdo Boycotters 'Pussies' http://t.co/LMAYRGmkKo pic.twitter.com/GyhBTRBpwp

— Breitbart London (@BreitbartLondon) April 28, 2015

– ‘Hang Rushdie’ –

In October 1988 Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi banned the import of the book, hoping to win Muslim support ahead of elections. Some 20 countries went on to outlaw it.

In January 1989 Muslims in Britain’s northern city of Bradford burned copies in public.

A month later, thousands of Pakistanis attacked the US Information Center in Islamabad, shouting “American dogs” and “hang Salman Rushdie”. Police opened fire, killing five.

Khomeini’s fatwa provoked horror around the Western world.

There were protests in Europe, and London and Tehran broke off diplomatic relations for nearly two years.

In the United States authors like Susan Sontag and Tom Wolfe organised public lectures to support Rushdie.

The author tried to explain himself in 1990 in an essay titled “In Good Faith” but many Muslims were not placated.

– Attacks –

Rushdie gradually emerged from his underground life in 1991, but his Japanese translator was killed in July that year.

His Italian translator was stabbed a few days later and a Norwegian publisher shot two years later, although it was never clear the attacks were in response to Khomeini’s call.

In 1993 Islamist protesters torched a hotel in Sivas in central Turkey, some of whom were angered by the presence of writer Aziz Nesin, who sought to translate the novel into Turkish. He escaped but 37 people were killed.

In 1998 the government of Iran’s reformist president Mohammad Khatami assured Britain that Iran would not implement the fatwa.

But Khomeini’s successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said in 2005 he still believed Rushdie was an apostate whose killing would be authorised by Islam.

Charlie Hebdo Journalist: ‘Islam Must Submit to Criticism’ https://t.co/9788GSlcYo

— Breitbart London (@BreitbartLondon) December 24, 2018

– ‘Islamophobia’ –

Many Muslims were furious when Rushdie was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2007 for his services to literature.

Iran accused Britain of “Islamophobia”, saying its fatwa still stood, and there were widespread Muslim protests, notably in Pakistan.

Rushdie was by then living relatively openly in New York where he moved in the late 1990s, and where his recent novels are set.

After many years living in the shadows, he became something of a socialite and is seen by many in the West as a free speech hero.

AFP —

Thirty years after Iran called for the killing of Salman Rushdie, the British novelist remains a figure of hate for extremists across the Muslim world, and though the level of outrage has dropped, the issue of blasphemy is as incendiary as ever.

Rushdie’s novel “The Satanic Verses” triggered mass protests from London to Islamabad and, analysts say, closed down the space for debate around Islam in a way that still resonates today.

Iran’s spiritual leader, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued the fatwa calling for Rushdie’s murder on February 14, 1989.

A day earlier thousands of protesters enraged by the novel’s publication had attacked the American Cultural Centre in Islamabad. Five people were killed in the ensuing clashes with police.

Pakistani journalist Shahid ur Rehman told AFP he was among the first to arrive on the scene that day, and watched as men stormed the roof of the centre and pulled down its American flag while police fired tear gas, then live bullets.

Rehman said the novel came as a rude shock to a Muslim world which was “basking in glory”.

Revealed: Counter-Terror Police Snooped on Newsagents Selling Charlie Hebdo – Breitbart http://t.co/0uVWIUDjnr pic.twitter.com/SnnvPrioxu

— Breitbart London (@BreitbartLondon) February 13, 2015

The Iranian revolution was just a decade old and the Soviet Union was on the verge of a collapse after being driven out of Afghanistan by the US-backed mujahideen, with Muslims in general and Pakistan in particular claiming credit for the defeat of an empire.

Rushdie’s novel, and the fatwa which followed, were “like a dam breaking”, Rehman said.

Today, the novelist is “hated as much… as he was hated back then”, said Pakistani religious scholar Tahir Mahmood Ashrafi.

But “people cannot protest consecutively for 30 years,” he added.

Anger over blasphemy remains effervescent among Islamic hardliners, however.

In the last ten years in Pakistan, politicians have been assassinated, European countries threatened with nuclear annihilation and students lynched over the issue.

The case of Asia Bibi — a Christian woman whose death sentence for blasphemy was overturned in Pakistan last year, sparking days of violence and drawing global attention to religious extremism in the South Asian country — is just the latest example.

Ashrafi said the publication of the novel “justified” laws against blasphemy — without them, he argued, “people like Rushdie will keep hurting the religious sentiments of Muslims”.

Police Catch Charlie Hebdo Arsonists Who Burnt Down Newspaper Offices – Breitbart http://t.co/kaveRtNGGs pic.twitter.com/JuJAN9g4tr

— Breitbart London (@BreitbartLondon) March 5, 2015

– ‘Catastrophic’ –

Even calls to reform the laws have provoked violence in Pakistan, and for some the fatwa helped blur the lines between blasphemy and intellectual debate across the Muslim world.

Analysts such as Khalid Ahmed, author of a book on Pakistan’s sectarian divide, say the fatwa marked the beginning of a “terrible decline” of intellectual discourse in Islam.

Khomeini’s call for blood was “catastrophic for the freedom of creation, literature and thought”, Egyptian journalist and novelist Ibrahim Issa said.

Other fatwas had been issued against writers in the past, he said — but usually by small, extremist groups. Khomeini’s was the first issued by an Islamic state.

“It was a dark moment that, thirty years later, reminds us how dangerous the interference of religion in freedom of expression (is)”, he told AFP.

Murdered Charlie Hebdo Staff Named ‘International Islamophobe Of The Year’ http://t.co/p7amjzvO8m pic.twitter.com/V0AcXL1hZB

— Breitbart London (@BreitbartLondon) March 9, 2015

Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei has on numerous occasions reiterated the verdict on Rushdie, most recently in 2015.

The Iranian government vowed it would not act on the fatwa in 1998, but such decrees are “not revocable”, Mehdi Aboutalebi, cleric and doctor of political science at the influential conservative think-tank Imam Khomeini Educational Research Institute in Qom, told AFP.

“Even if 800 years pass, the sentence remains the same,” he said.

The fatwa has caused multiple diplomatic rows over the years — as have other cases of blasphemy, such as the controversy over satirical Danish cartoons of the Islamic prophet printed in the right-wing Jyllands-Posten newspaper in 2005.

Politics and religion are often intertwined in Iran, Aboutalebi explained, echoing a sentiment expressed in other Muslim countries.

“For instance, Iran’s quarrel with US is not over money or economy…. This is all about our beliefs and our religion,” he said.

The fatwa shows “we will not tolerate anyone breaking our belief boundaries”.

Today the furore over Rushdie interests only “the most radical ayatollahs”, said Clement Therme, research fellow at the Iran International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Iranians are experiencing “revolutionary fatigue”, he said, as Tehran hunts for friends amid criticism over its regional policies and disputed nuclear programme.

“In a context of increased isolation of Iran, realpolitik requires Iranian leaders to avoid escalation on this issue,” Therme said.

In Pakistan, where Rushdie’s books have been available on the black market for years, “Joseph Anton: A Memoir” — which recounts his time in hiding after the fatwa — is quietly but openly on sale in at least one bookstore in the capital.

However most booksellers remain cautious.

“There is a religious issue,” one of them, who gave his name as Ayaz, told AFP.

“That’s why we can’t display (Rushdie’s books) and also can’t order them.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.