More than a thousand bearded men, muffled in scarves and accompanied by veiled women, stand under the hot sun, waving black and white flags and chanting “Allahu Akbar!” (God is Greatest).

This is not a scene from the Middle East or Central Asia but a rally of the supporters of the Islamist Hizb ut-Tahrir (Party of Freedom) in Simferopol — the capital of the Ukrainian Black Sea region of Crimea.

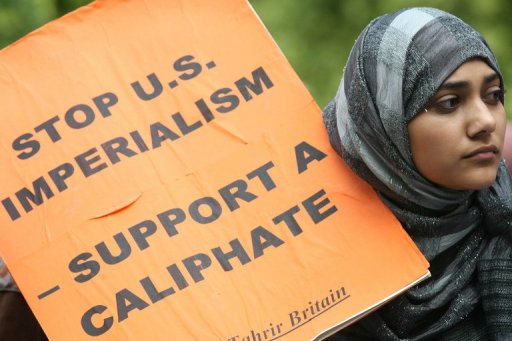

Hizb ut-Tahrir seeks to re-establish a Caliphate — a pan-Islamic state based on Islamic rule like in the medieval era — across the Middle East and Central Asia.

Banned in several states, it is now showing surprising strength in Crimea, a balmy seaside holiday resort region which has its own substantial Muslim Tatar minority.

The head of the information office of Hizb ut-Tahrir in Ukraine, Fazyl Amzaev, told AFP that the party’s ambition of reviving the Caliphate does not extend to Ukraine and its presence is educational.

The first devotees of Hizb ut-Tahrir appeared in the Crimea in the early 1990s. Twelve percent, or 250,000 of the nearly two million inhabitants of Crimea are Sunni Muslim Crimean Tatars.

Now they number between 2,000 and 15,000 — Hizb ut-Tahrir does not disclose the true number, claiming only a permanent climb in supporters.

— ‘Democracy is a system of unbelief’ —

Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami, established in 1953 in East Jerusalem, has been banned in Russia and several Central Asian countries. It is also outlawed in Germany due to anti-Semitism and anti-Israeli propaganda.

The Spiritual Board of Muslims of Crimea — the main umbrella group for Muslims in the region — has already called on the authorities to take a closer look at the group’s work in Ukraine.

Its deputy head Aider Ismailov told AFP that Hizb ut-Tahrir’s teachings can contradict local religious tradition and practices.

Ismailov is not pushing for the party to be banned in Ukraine, but he considers its ideology harmful.

Ukraine appears in no hurry to ban Hizb ut-Tahrir, if just because the group simply does not exist in the legal framework of the country — it is not registered either as a party or as a public or religious organisation.

Party members themselves do not seek for their formalisation, citing ideological reasons.

The authorities so far have taken merely small steps to avoid possible confrontations between Hizb ut-Tahrir members and their opponents, in particular with court decisions trying to ban party rallies.

In June, a court approved a suit from local authorities banning a scheduled rally that could not guarantee order.

Despite the prohibition, the action took place, and the police, as in similar cases in the past, limited themselves to drawing up a protocol on an administrative law violation.

The Crimean members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, however, also behave with extreme care to prevent possible attacks from opponents and punitive actions by the authorities.

In Simferopol, they have no headquarters and their information office is a virtual concept not linked to any postal address.

Amzaev is however a prominent public figure, giving interviews, speaking on television, writing on social networks, and recruiting supporters.

During the last rally of Hizb ut-Tahrir in Simferopol, almost every speaker called on fellow Muslims to aid the Syrian rebels battling the regime of Bashar al-Assad, which sparked protests in the Crimean Tatar community against the possible sending of militants to Syria.

Amzaev said: “We are not recruiting the rebels, but I do not rule out some of the Crimean Tatars fighting against Assad.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.