CARACAS, Venezuela – “Are you paying with bolivars or foreing currency?”

You will be hearing that question pretty often if you go to any supermarket or store in Venezuela these days. In this new chapter of our lives under the socialist regime, the U.S. greenbacks are king, more so than ever before.

The easing of the once-fierce foreign currency controls imposed upon the country in 2003 has opened the way for Venezuelans to stop hiding their use of American money. Socialist dictator Nicolás Maduro has cataloged the decision to allow the use of the so-called enemy currency as an “escape valve” for the economy. In doing so, he has thrown the most die-hard adherents of Hugo Chávez’s Socialism of the 21st Century into an ideological crisis.

The policy means we’ve gone from years of severe shortages of items, massive lines, fingerprint scanners, and ID-card based rations to a new era where the types of currency you possess determine what headaches you get to suffer through.

Whether you’re able to pay for things in foreign cash or have to rely on the constantly devaluating Venezuelan bolivars, each has its own peculiarities. What follows is a brief primer on how people are paying for things down here in this post-collapse era.

Paying Using U.S. Dollars

Today, a Venezuelan customer can pay for almost everything with foreign currencies without fear of getting arrested. We’re now living under a pseudo-dollarization of what’s left of our country’s economy — in other words, a little bit of capitalism to breathe some life into the corpse of our socialist economy. Some receive it as payment for their jobs in the private sector or as an independent worker, others through remittances from friends and family abroad.

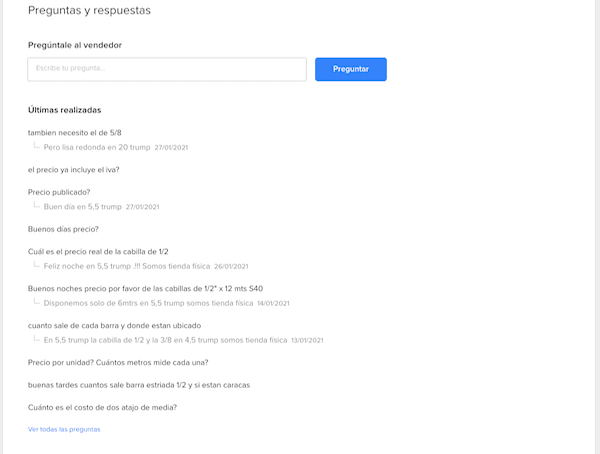

It is no longer necessary to conduct clandestine exchange operations or employ code words or pseudonyms in messages to pay for things using American or European currencies. For a long time, it was outright illegal to even mention the existence of parallel exchange rates other than the regime’s official one, to the point that people began to refer to dollars as “verdes” (greens), “lechugas” (lettuces), “Obamas,” “Trumps,” and, I suppose, “Bidens.”

Screenshot from mercadolibre.com.ve where to this day, the word “Trump” is used to refer to U.S. Dollars to fool the censorship that the regime once forced the website to implement on anything remotely close to “Dollars.”

For those who live in Venezuela, keeping U.S. dollars safely hidden away at home has been the main method to preserve some purchasing power, especially during the disastrous years of Nicolás Maduro’s rule, where hyperinflation and socialist mismanagement have destroyed our currency not once, not twice, but three times now.

Since cash bolivar banknotes are hard to find these days (and outright worthless), the U.S. greenbacks have become the de-facto cash currency here. The regime’s official currency exchange is now close to the myriad of “black market” rates that exist — but don’t think for a moment that using them is as smooth as in America.

If you pay with dollars, then expect your bill to be heavily scrutinized, inspected, and, in many cases, passed through a counterfeit detector before its amount and serial number is scribed on each commercial establishment’s daily dollar logs — all of which does end up consuming its fair share of time. It is pretty common to see a specific staff member or two assigned to perform this particular function in a supermarket or store.

Many, if not almost every commercial establishment, will not accept your U.S. banknotes if they so much as have a tiny scratch or minuscule pen scribble on it. Many people have stored a handful of foreign currencies for more than a decade that do end up deteriorating over time, and it’s not like we can simply walk to a U.S. bank and exchange old bills for a newer one. With luck, you may find a place or two that’s less strict when it comes to the state of your cash.

This attitude towards old greenbacks has opened the way for a new type of exchange entrepreneurship: men and women who will take your “problematic” bills for a fraction of their value and give you something you can use. Some, out of desperation or necessity, end up doing this, because at the end of the day, something is better than nothing, and there’s food to be bought and mouths to feed, even if you’re losing money as a result.

I’m pretty sure that American citizens in the U.S. are accustomed to purchasing something that goes for, say, $4.35, by giving the cashier a $5 bill and getting $0.65 in return. That’s not something that happens here. Pennies and coins are not accepted anywhere, and low-denomination U.S. bills are rare to get a hold of. Certain prices are simply rounded up around this limitation. While you may no longer have to wait in line for toilet paper, you’ll now find yourself having to wait for the supermarket to have enough change for you.

Another scenario is one that I can best describe through this example: Let’s say you got your hands on a $20 bill and there’s some stuff you need to buy for your family, but the total comes up to $18.50. What do you do? You have to make a choice.

You could purchase some extra things to bring your total to an amount slightly above $20, use your bill to pay, and cover the remaining difference with bolivars. Alternatively, you could pay up to $15 using your $20 bill, pay the rest in bolivars, and the supermarket gives you $5 back — if they have one in hand, otherwise you have to stand there and wait and see if someone pays with a $5 bill. You no longer have to wait in line for toilet paper – now you need to wait for the supermarket to have enough change for you.

Foreign credit cards are accepted in certain places as well, as our local ones are beyond worthless. Electronic payment processors have also become widely accepted as a form of payment, some more than others.

Zelle, the United States–based digital payments network, has become the preferred electronic payment method in the country for many commercial establishments. Other processors, such as PayPal and Venmo are also accepted, but to a drastically lesser extent.

A store in Venezuela advertises that it accepts payments through the American online system Zelle. (Photo: Christian K. Caruzo)

Naturally, the majority of the country does not have access to the Zelle platform, as this is a service that requires its users to have a bank account in a corresponding U.S. banking institution, which requires traveling to America — and traveling to America requires a U.S. visa, which not everyone gets to have. Zelle has become a quick way for people outside these borders to help pay for goods and services for people living inside.

Regardless of how you do end up paying in U.S. currency, expect your receipts to show bolivars instead. The socialist regime of Venezuela wants to heavily tax foreign currency transactions to get their hands on people’s hard-obtained foreign currency, so this is a way to “fool” the system.

Paying with Bolivars

There are many who do not have access to foreign currency, and thus must continue to rely on and pay using the undead remains of the Venezuelan bolivar, a worthless currency that nobody wants, not even the socialist revolution that murdered it. Yet, this is, after all, the country’s legal tender, and because we’re not a completely dollarized economy, it’ll still live on in some way.

Using bolivars to pay for things here is the same old experience. While you don’t have to deal with any of the nuances of paying with cash U.S. dollars, hyperinflation makes holding bolivars in your bank account a fool’s errand, as the currency rapidly loses its value daily, sometimes within a manner of hours, or even minutes

Whether you just got paid the regime’s misery monthly minimum wage of Bs. 1,200,000 (roughly $0.67 per month, most definitely less by the time you get to read this) or a higher amount, you need to get rid of your bolivars as soon as possible, because that orange juice that you like so much might cost 50 percent more next week.

The worthlessness of our currency has turned it into a digital currency for all intents and purposes. Bolivar banknotes are hard to come by. Our current highest banknote, the Bs.50,000, is worth less than $0.03, and outright useless when everything costs millions these days, so its only real value comes as a collector’s item, a souvenir of our socialist tragedy.

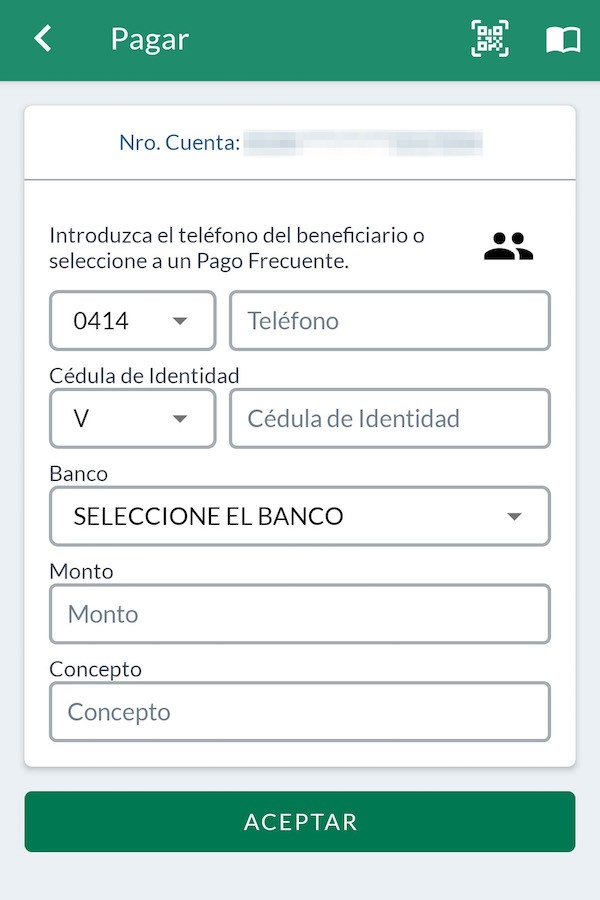

We all have our own “Weimar wheelbarrows,” they just happen to be easier to carry thanks to the wonders of today’s technologies. The bolivar is moved and used to pay through the country’s banking network mainly via debit cards and wire transfers. The need for a quicker and more efficient way to move bolivars between different banks and persons prompted each Venezuelan banking institution to develop their own proprietary peer-to-peer payment smartphone applications interconnected with other Venezuelan banks.

One of the several apps banks have come up with to quickly move millions of Bolivars between people.

To put in the worthlessness of the bolivar in perspective, virtual video game currencies are more stable and valuable, something which I’m most familiar with, as once upon a time I used to “farm” one of these video game currencies and exchange it for U.S. dollars so that I could be of help for my mother in her one-sided fight against cancer. Between you and me, it was more money than what I was making at my regular job at the time — that’s how worthless the bolivar was and continues to be as a currency. An infinitely spawning resource, such as a video gamer’s virtual currency, is more stable than the currency of the country with the world’s largest proven oil reserves — a feat that is only possible through Bolivarian and socialist revolution, a motto that the regime often plasters on its achievements.

Regardless, there are things that, no matter what, you must pay for in bolivars, such as public utilities and bus fares. Maduro has announced a move to a “100 percent digital economy” but, in practice, this is what we’ve been doing with the bolivar for the past two years. This upcoming shift to a “digital bolivar” is a necessity but, in a country with a collapsed power grid and unstable internet connectivity, a digital economy might cause some headaches in the future.

The events of the 2019 blackouts are still fresh in our collective consciousness. During those long and dark days, the bolivar ceased to exist, as nobody was able to access their bank accounts or use the internet. That was when the U.S. dollar truly became the country’s main cash currency.

It only takes one blackout or one disruption in your internet service to leave you unable to access your bolivars — and we’ve already had a few this year.

Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies are another life-saving form of payment here, but it is not something your average citizen will partake in, so it’s best left to the more tech-savvy and for those willing to wrestle with the constant power and internet failures that plague this country. While not that widely used yet, plenty of places have begun to accept it, from butcheries to tech stores to even fast-food chains.

Mining cryptocurrencies is an activity that many have partaken into as a means to survive, but there was a time when this practice was highly risky and many got arrested for it, not to mention that the socialist regime of Venezuela expects you to register with them if you’re into mining.

As for the regime’s own scam cryptocurrency, the Petro, it can be safely added to the list of failed experiments. The regime tried to push it in December of 2019 but, after that initial rush, it simply faded away.

For a normal citizen, the Petro’s main raison d’être is to make getting out of the country more expensive with each passing day, as the costs of passport and apostille services are anchored to this cryptocurrency.

The ongoing tales of the collapse of socialist Venezuela have had many peculiar and unique chapters, some coated in an absurdity most nonsensical, while others have been nothing but abject tragic in nature. While our anamorphic lives rapidly contort and adapt to every new woe, there has always been one constant: The U.S. dollar is the one thing holding this place together, now more than ever.

Time and time again, the Bolivarian Revolution has waged an ideological war against the American currency.

“If they pursue us with the dollar, we’ll use the Russian ruble, the yuan, yen, the Indian rupee, the euro,” Maduro said in 2017, back when he sought to “free” Venezuela from the tyranny of the dollar. Fast forward a couple years, and you have the same socialist dictator thanking God for a dollarized Venezuela.

Venezuela’s Vice President Delcy Rodriguez recently stated, “Venezuela’s monetary policy is the bolivar, there is no room for dollarization.” Yet, the once demonized and outright illegal American currency has become life-saving, instrumental in the continued survival of those who live within these borders.

Ultimately, it is outright ironic, if not poetic, that after years of demonizing the U.S. dollar, it is the one thing that Maduro’s regime is desperately starved of to stay in power. This perceived victory of the American currency over the remains of our economy is not an admission of defeat for them, but rather, a necessary evil for the continued existence of their socialist rule.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.